Why K League Teams Use a Back-Three

Over the last few seasons, the back-three formation has gained popularity throughout the K League with a number of teams opting to employ it to some degree and to varying success. Football coach and BIJFL coordinator for China Club Football Michael Booroff looks into the benefits and pitfalls of such a strategy and why particular clubs are opting to use it.

The modern game has evolved to such a state that identifying formations has almost become redundant. At any point in any game, a team can look completely different to that of their formation. There are some many variables and so much variation in football that a formation is really only used to apply some simplification and give a level of basic understanding of how a team will line up in relation to the opposition.

Formations are by definition subjective, volatile & only used to cut down the solution space to simplify a bit, whilst interacting with opposition('s 'formation'). Our 4-d-2 has 11 different variations out of possession, for instance, just in terms of base staggering. https://t.co/Jow0tyRv0U

— René Marić (@ReneMaric) February 23, 2019

The distinction between a back three and a back five is hard to make due to the fluidity of a team in all phases of the game. One moment it can look like three defenders. Suddenly in can become five.

According to FBref.com, of the 324 starting line ups in 2020 K League 1 season, 114 have used either a back three or five. These have come in variations such as 3-5-2, 3-4-2-1 and Seongam’s 3-3-3-1. This is quite an interesting trend given that about five years previous, the use of three central defenders was almost obsolete in world football.

Within K League 1, the use of a back three (or five) can be split into 3 main categories: 1) teams that don’t use a back three/five (Ulsan, Jeonbuk, Pohang, Busan), 2) teams that have used it sporadically (FC Seoul, Gangwon) and 3) teams that exclusively use a formation including it (Deagu, Seongnam, Incheon, Suwon). The latter category is the most intriguing, as only Deagu found themselves in the final round A come the split.

With over a third of starting XI’s using three centre backs, and with five of the bottom six sides having used a variation of this set up this season, this article will look at the reasons why a back three/five benefited these teams. While there is a benefit to their use, the potential pitfalls will be explored, and will probably be more salient due to these teams being at the lower end of the table.

Emergence of Three

By the early 00’s, the use of three central defenders had become almost redundant. With teams now favouring a single forward formation, withdrawing a player into midfielder to create overloads and looking to control possession, three central defenders were no longer required to deal with a single striker. If three central defenders were needed to deal with just then one striker, then this meant that teams would be underloaded in other areas of the pitch. With the rise of the 4-2-3-1 this often meant a team using a back three would match up with an underload in midfield (often a 2v3).

More recently, the use of a back three has seen somewhat of a renaissance. To most football fans, the re-emergence of this formation has been through Antonio Conte and his change to a 3-4-3 at Chelsea that eventually led to them becoming Premier League champions. In K League 1, this was a trend that was starting even before Chelsea. K League United’s very own Ryan Walters and Scott Whitelock had commented on how a raft of K League teams (most notably Suwon) had been using a back three in games.

That seems the popular theory but Suwon (as many other teams) we're playing 3 at the back before Chelsea were!

— Scott Whitelock (@scottyonfire86) April 7, 2017

Overloads

So why would these formations have benefited the teams nearer the bottom end of the table? One of the main reasons being the ability to create overloads nearer a team’s own goal. This can be useful both in and out of possession. For teams that are looking to build-up and control possession, the additional defenders in the first line have the ability to create an overload vs opposition attackers. Depending on how the opposition pressure the ball in the first phase, this will most commonly create situations such as a 3v1 or 3v2. While this may reduce the number of players higher up the pitch, the logic here is that the extra security nearer your own goal will help maintain possession of the ball but also reduce the threat of a counter-attack if the ball is lost due the extra players in defensive positions.

In K League 1 this season, Examples of this overload can be seen from both Seongnam and Suwon. In Seongnam’s matchday 17 game vs Ulsan, the use of a back three (in their 3-3-3-1 shape vs Ulsan’s 4-1-4-1) allowed opportunities to advance the ball into midfield. With Yeon Je-woon in possession of the ball, when Junior goes to the pressure the ball there is two simple passing options to help maintain possession. With only the one pressuring forward, this provides either Ahn Young-kyu or Im Seung-kyum with the time and space to carry the ball into midfield. Should an Ulsan midfielder move to support Junior and pressure Seongnam’s defensive line, additional space is now created in midfield that they can look to exploit.

In the most recent super match, Suwon were also able to show how the use of a back three could create a natural overload to help advance the ball. With FC Seoul defending in 4-2-3-1/4-5-1 shape, when one of the Seoul midfielders moves forward to help pressure, this still leaves a free defender. In this example, it’s Yang Sang-min who has enough time and space to carry the ball before playing a penetrative pass.

This overload is also beneficial when defending. For teams lower down the table. The importance of not conceding cannot be overstated. In low-scoring games when your team is having trouble putting it in the back of the net, more importance is then placed upon the team out of possession to make sure a goal isn’t conceded.

To increase the security near a team’s goal, an increased number of players in the defensive line can be beneficial. With team’s using three central defenders, and overload can naturally be created against a team playing with either a front two or lone striker. While this was a cause of the demise of the back three previously, this is now something that can be used in a beneficial way to deal with elite-level forwards. While it will mean that a team will have one less player elsewhere to defend, this does, however, offer added protection near a team’s own goal.

Before the split, this was often seen from team’s playing against Ulsan in their 4-1-4-1. This is also of importance due to the quality of the lone striker, Junior. Having the extra central player in a defensive position can help share the responsibility of defending one of the best forwards in K League. If any player needs to mark Junior or move out of position to track his movements, there is still two players in position to defend and cover the space in central defensive areas.

Lack of Attack

For all the benefits of using three central defenders, the teams that have used them in K League 1 have for the most part found themselves nearer the bottom end of the table. While a benefit can be seen in build-up or when out of possession, often there are issues in the way a team attacks (or lack thereof).

In Tifo’s video on the use of a back three, they note the importance of the quality, fluidity and guile needed from the attacking players. With teams who play a back three having the ability to get many players behind the ball (to try and nullify opposition attacks), it’s often up to these limited attacking players to create something almost out of nothing. If teams lack a certain attacking quality, the onus then switches to them being more adept at defending and stopping the opposition from creating chances.

It should be noted that the teams who usually deploy a back three/five are in the lower rankings when it comes to average possession this season. Suwon rank 7th (48.9%), Seongnam 9th (47.7%) and Incheon 11th (45.7%). Even Daegu in Final group A, and having secured Champions League football next season, rank 10th with an average of 46%.

For all the use of having players near the ball to create overloads and secure possession of the ball, it often creates scenarios like the one below for Seongnam. With seven players either in line with, or in front of Suwon’s forwards, it’s up to three players to break down the rest of Suwon’s defence.

This is why teams that play like this are reliant on one or two attacking players who are able to change the game in their favour. Daegu is a perfect example of this. While they play with three central defenders (and often in a back five out of possession), they have forwards such as Cesinha and Dejan Damjanovic who are able to create something out of seemingly nothing.

Defensive solidity

Linked to the above, the ability for a team to take up an organised defensive shape is also beneficial for teams fighting the drop. With the wing-backs dropping into the same line as the central defenders, a team can have a backline of five that can easily defend the full width of the pitch. Ahead of that, there is the option to have a midfield line of three or four, additional security and denying the opposition from playing into central areas of the pitch.

In the Coach’s Voice’s ‘Ask The Coach’ series, Chelsea academy coach James Simmonds talked about the use of a 3-4-2-1 formation. When talking about the benefits of this formation, he mentioned how if the team can organise properly, the opposition will have difficulty playing through the defensive block:

‘Defensively, if you really set up properly, you’re really hard to beat because you can revert to a 5-4-1 and you’re really hard to break down if you get it set up right.’

Tobias Hahn also discussed the merits of a 5-3-2 and how its forms can be difficult for opposition teams to break down. In his tweet thread, he noted that with the increased number of players in central areas (3 midfielders and 2 forwards) ahead of the defensive line are able to increase the difficulty in playing through the centre as these players are able to cover the passing channels in this area of the pitch. Also, with this organised shape, each player can cover the space around the player in front of them.

THREAD (Part 1) - How would you attack against a 5-3-2?

— Tobias Hahn (@hahn97_t) September 21, 2020

Besides the back-five, the 3-2 structure in the centre is the defining characteristic of this formation. The diagonal structure makes it quite complicated to overcome the lines because each player pic.twitter.com/OKKMznUCXm

Concede Space

Nearer the bottom of the table, it could be implied that teams at the lower end will spend more time defending than they would attacking. As mentioned previously, the possession statistics for these teams ring true here. The focus then shifts towards maintaining defensive solidity and reducing the possibility of opposition turning this possession into threatening chances.

While using three central defenders with the wing-backs dropping back to create a solid, and well covered, defensive line, it also poses the risk of allowing opposition teams increased space. Teams will often look to take up their defensive position almost immediately after a turnover, rather than trying to win the ball back in a counter-pressing situation.

While this is not a problem in itself, it does allow for additional attacking pressure to be put on by the opposition. In the example below for Seongnam, dropping deeper to form a low block can allow them to get organised defensively early. However, by dropping this deep towards their own goal, it provides Seoul with space in more advanced positions. With the defenders being in possession of the ball this is not such a dangerous position, but due to the proximity to the goal (being in the opposition’s half), one pass can put them into an advanced position with the chance of creating a scoring opportunity.

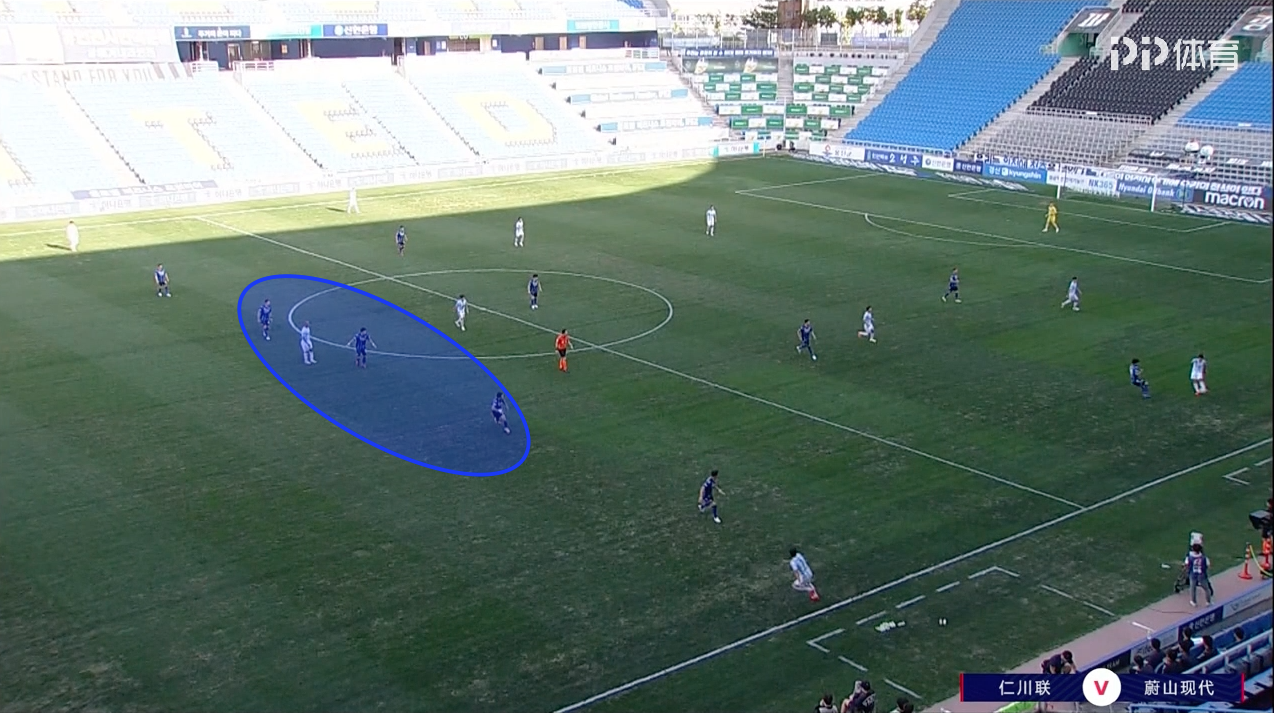

This can be seen in a less extreme example with Incheon, this time against leaders at the time, Ulsan (matchday 22). As soon as the ball is turned over, Incheon drop into their own half to form their organised block. While the space they concede is not in as an advanced position as the Seongnam example, it still allows ease for Ulsan to bring the ball out from the back under little pressure.

Use of Two Strikers

Further upfield, as mentioned in Rhys Desmond’s article on the rise of the 3-1-4-2 formation, the use of a back three can also help accommodate two central strikers. With a formation such as 3-1-4-2 or 3-5-2, the use of a back three allows a team to maintain three players in central midfield, whilst freeing up an additional player that can play in a forward position.

This is particularly important when viewed through the prominence of 4-3-3 and similar lone striker formations. With teams across the globe being more inclined to use a three-man forward line or a lone striker, consequently, this has meant that a player who would usually play centrally would now have to be accommodated by being pushed into wide areas of the pitch (to play as a winger/wide forward) or not playing at all! A classic example of this would be Thierry Henry at Barcelona. In order to accommodate Lionel Messi as a central forward/false nine, Henry would be required as a left-winger in order to play and be of service to the team.

Heading back again to the super match, Suwon’s use of a front two was able to cause numerous problems for FC Seoul’s back four. With both forwards, Adam Taggert and Seek Hee-Han, positioning wider than a usual front two, they are able to engage both centre backs and exploit the space around them. In the below example, Min Sang-gi plays a diagonal pass into the space vacated by left-back Ko Kwang-min (who has moved upfield to pressure the right wing-back, Kim Tae-hwan). With the increased space between both centre back and left-back, the centre backs are now forced into a dilemma where they have to defend the space vacated by the full-back, cover each other and have access to the opposition forwards. The diagonal pass here helps increase the distance between the two and create two 1v1 situations for Suwon.

So Why?

With the potential benefits and pitfalls of using three central defenders, why do so many teams in the bottom half of K League 1 use them? It could be explained by the current trends in world football. Now coaches have seen other teams garner success using a back three or a back five, they are more inclined to use it themselves to get a much needed three points for their team. Going back to Tifo’s video on the back three, the unfamiliarity aspect in the past has often deterred coaches from using it. This is less so now.

It could also be, as Ryan also points out in his tweets (see the above twitter thread with Scott), the fact that K league coaches need to appear to be ‘doing something’. Coaches using traditional formations can be deemed to not be trying hard enough, and the use of something like a back three can be viewed by fans to be a step towards being proactive in the search for wins to help their team move up the table.

The Final Round

Probably the biggest factor with teams at the bottom of K League 1 using three central defenders is the difference between being proactive and reactive in the way they play. Jonathan Wilson’s article from 2016 (but still relevant) coveys this message, teams are often proactive when looking to control possession, whereas teams who look to play mostly without the ball and counter-attack are deemed reactive. Most of the drawbacks related to often using a back three revolve around being reactive and looking to avoid losing rather than trying to be on the front foot and attacking.

But when K League survival is on the line, teams are more likely to throw caution to the win and be proactive in order to win. This was the case for Incheon in their win v FC Seoul, which ultimately kept them up. Comparing the below example to previous ones when out of possession, Incheon’s defensive block is already higher up the pitch, reducing the amount of playable space Seoul have:

And in need of a goal, the difference can be seen in the number of players they allow to commit to the attack:

|

Now that the season has ended, and team’s such as Incheon and Seongnam have secured themselves another season in K League 1, will they look to be more proactive with a back three next season? Will this change after some bad results? With two relegation places now back on the table for next season, will the fear of the drop force them into a reactive style of play to avoid losing? We’ll have to wait until next season to find out.

![[about]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh0mXcKy7h0fXIgdvWFm5DpFfwXkPr2ggzUt9_AoPo8vS0HOsFMT8KsO21qTLZBKoLyQXSOAckzy4OtJCPOoHtL5cGqAa0zXKzIdiW45D6TCFAisfJUODssBTfrkat95GXhJc8haWSP3nyV/s1600/KLU.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment